When I was growing up on a small farm in Virginia we used untreated biochar on struggling soils, though we didn’t call it biochar then. I was told that it should only be used on weak soil that we weren’t using for cash crops in the next year or two. We’d plow it in after harvest, and the next spring I watched as the weeds and wild annuals that pioneered that land came up anemic, stunted and off-color. Given a year or two fallow, the biochar resulted in strong improvements in crop health and yield when we finally did replant it.

We now know that biochar without inoculation is like a sponge that absorbs soil nutrients until it develops equilibrium with the soil. Only then is its promise realized. But lying fallow for two years isn’t needed – if you inoculate biochar ahead of applying it, your soil will improve almost immediately.

Biocharging (inoculating) the biochar is simple and easy. Doing so actively accelerates soil recovery and the associated microbiology. For example, a 2014 study published in Soil Biology & Biochemistry1 shows that biocharging greatly accelerates growth of mycorrhizae, which penetrate plant root cells and improve uptake of soil nutrients including nitrogen and, in particular, phosphorus – which can typically be difficult to retain in soil. In the study, they determine that inoculating the biochar results in three times the growth of mycorrhizae than in untreated biochar. Similar studies have been done for other microbiology.

This may sound complicated but, rest assured, just about anyone can easily make biochar at home (or buy it), and inoculating it doesn’t have to require any more equipment than a shovel or pitchfork.

Making biochar is a relatively simple process. Wood or other biomass is burned in a low-oxygen environment causing pyrolysis, changing its chemical and physical composition. The end result is a nearly-pure carbon material that will last in your soil almost forever.

According to Michael Low of Green Fire Farm2 in Vermont, “The easiest method [of making biochar] with common materials is the T-LUD [top-lit updraft] stove … These usually employ a 55 gallon (210 litre) drum and some variety of hardware for drafting and gas flow.” His favorite design is the Hookway Retort,3 which is simple and easily built with local materials, but many designs have been published. YouTube is a goldmine for additional ideas on producing biochar.4

Many people purchase commercially-produced biochar such as that made by the craftsmen at Vermont Biochar,5 for several reasons. First, because they use more advanced tools and techniques than the home producer can easily acquire, commercially-produced biochar is usually more consistent in composition and charred under ideal temperatures.

Second, they are able to produce inoculant tailored to specific uses. Vermont Biochar, for example, produces (by hand) several versions ideally suited for either leafy annuals, root crops, or shrub or woody perennials. Each uses a different composition of inoculant to tailor it for the specific application.

If you can make biochar* on your property however, it’s probably best you learn how, and to stack functions of your waste residue in keeping with permaculture principles. What biomass you make your biochar with is far less important than how you biocharge it.

Even commercial biochar producers say their products benefit from being biocharged again once it’s on your property, to tailor it to your site conditions. Here are two easy methods you can do at home.

Compost charging

The simplest and most efficient method to biocharge your biochar is to simply mix it into your compost piles, stacking functions to benefit both the biochar and your compost. Even if you buy inoculated biochar, rather than producing it on-site, it will be improved by maturing in your compost. You can use as much biochar as you want, up to about an even 1:1 ratio with the compost, so don’t worry too much about overdoing it.

Thayer Tomlinson of the International Biochar Initiative,6 seeking to foster economically viable biochar systems that will safely enhance soil fertility and function, emphasizes the value of inoculating biochar in the compost pile:7 “For the biochar material itself, undergoing composting helps to charge the biochar with nutrients, without breaking down the biochar substance in the process.” Better still, there are benefits for the composting process, which “may include shorter compost times; reduced rates of GHG [greenhouse gas] emissions; reduced ammonia losses; the ability to serve as a bulking agent for compost; and reduced odor.”

If you use the compost method to biocharge, some experts also recommend adding both manure and bones (preferably broken up first, but not necessary) to your compost pile. In the Amazon, they used biochar, manure and bones to make Terra preta8 – and it remains extremely healthy soil to this day.

Quick tip: If you have time, a great way to get the most out of your biochar is to spread it an inch thick or less into your farm animal bedding. Then, when the bedding is spent, add it to the compost pile. The biochar is essentially ‘double-charged’ in this way. Also, in addition to stacking functions of your animal bedding, this can help reduce odors. Anecdotal evidence suggests it can also reduce illness among your animals!

Rapid charging

The other way to inoculate your biochar is a bit more labor-intensive, but you can complete the process in hours or days, not months. First, fill a 55 gallon (210 litre) drum with fresh water and biochar. If you are using municipal treated water, let it sit for a couple days to remove any chlorine. Then add compost tea or worm castings and leachate to the barrel with some soil from the area where you will use the finished biochar. For example, if you are going to apply the biochar to your fruit orchard, add some soil from around a robust and healthy tree in that orchard. This will help charge the biochar with the ideal microbiology for your specific orchard.

Once everything is well mixed, insert a long tube such as a length of PVC pipe into the barrel and direct air from a blower into the tube, or use a pond aerator and air stones. Aeration supercharges the inoculant and gives the beneficial microbes a massive head start, and helps them adhere to the biochar. Continue this for 12-24 hours.

Once your chosen procedure is complete, your biochar is properly biocharged and ready for you to apply it to the area you’ve selected. You can repeat this process annually, although it might be better to apply biochar to new areas with each batch so that as much soil as possible is amended.

There are two primary ways to effectively apply biochar:

Tilling application

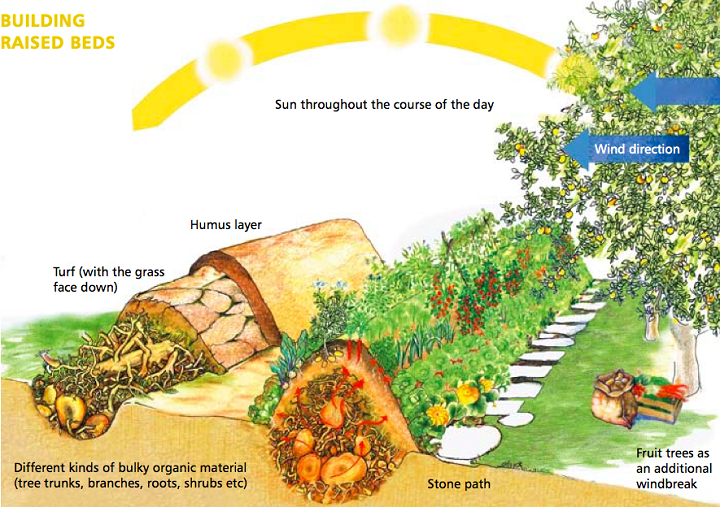

Spread pure inoculated biochar about a ¼in (6mm) thick on the soil before normal tilling. Do this at the same time you till in your other soil amendments. It’s that simple. For larger areas such as pastures, the ideal amount of biochar to till or disc in is one ton per acre, but if you don’t have that much, spread out what you have and add more each time you amend the soil.

No-till application

You can spread pure inoculated biochar around a grow area, then mulch as normal to hold the biochar in place. It takes about 10 pounds (4.5kg) of biochar to properly cover 100 square feet (9.3m2). For potted plants, use pure biochar at a ratio of about 1:16 with your potting soil – about ½ cup per gallon of soil (118ml per 4 litres of soil). This ratio is good for raised beds as well, one gallon (4 litres) of biochar per 16 gallons (64 litres) of soil.

In all cases, till or no-till, if you inoculated biochar in compost (at ratios up to 1:1, remember), just apply compost as normal – the presence of biochar doesn’t change the amount of compost used.

Highly flammable gases are released during pyrolysis, so make it outside, well away from buildings, animals and people!

References

1 A mycorrhizal fungus grows on biochar and captures phosphorus from its surfaces, Soil Biology and Biochemistry, Volume 77, October 2014, pp.252-260

2 www.vermontbiochar.com

3 www.facebook.com/hookwaycharcoalretort

4 www.youtube.com/results?search_query=how+to+make+biochar+at+home

5 www.vermontbiochar.com

6 www.biochar-international.org

7 The use of biochar in composting, Marta Camps, Massey University; and Thayer Tomlinson, International Biochar Initiative, February 2015

8 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Terra_preta