Something I love about permaculture is the way it can help us transform barren, problematic or empty spaces into rich, productive and inspiring versions of what they once were. Over twenty-five years ago, I saw that happen to my garden in Bristol, which started out as a car park covered in concrete slabs and before long became an inner-city oasis generous in its offerings of fruit, herbs and nuts. Since then, my main focus with permaculture has been on Zone Zero Zero, applying design choices and skills to the inner landscape of our hearts and minds. So what might a permaculture-inspired makeover look like when applied to something that many might find either missing or misleading in the difficult times we face – the concept and experience of hope?

“Hope is the feeling that things are going to get better,” said my friend Fernando. How can people have that when they grapple with the disturbing realities of climate change or the prospect of societal collapse? In the discussions I’ve been part of, a view becoming more common is that hope can be a misleading comfort. Some even call it ‘hopium’. A starting point for redesign is to acknowledge where and how hope can be misplaced. A teaching tale is of Donald Trump in mid-March 2020 painting an optimistic picture of churches full at Easter, which at the time, as COVID was beginning to take off in the US, was just a few weeks away. His desire to strike a hopeful note fed a complacency that contributed to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people.

My good friend Sarah Pugh, a permaculture teacher in Bristol, taught me about another side of hope. As a student of ecology, she’d got accustomed to the sad sequence of human impact that starts with forests and ends up with deserts. It was watching a slide show revealing the reverse was possible too that started Sarah on the permaculture path. What got planted in her heart-mind that day was a compelling sense of possibility that changed her life. This is a different kind of hope – a guiding energy and purpose that can happen through people when they know in their hearts what they hope for.

How can we benefit from the enlivening inspiration of guiding hope, without being lulled into the false sense of security of hopium? In our book Active Hope, Joanna Macy and I describe a three-step process. First, you start from where you are, taking in an honest appraisal of what you face and how you feel. This is about being reality orientated. That can lead to a recalibration of hopes, where you let go of options no longer available or as desirable. We’ve all had to do a lot of that with the lockdowns of the last year. The relinquishing of carbon-heavy hopes is part of how we address climate change.

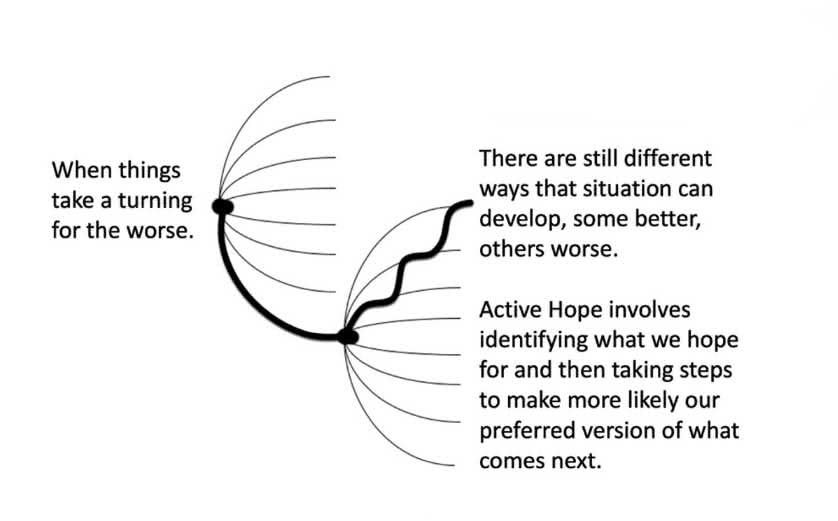

I illustrate the second step of active hope with an image I call ‘the Spider Diagram’. Imagining a spider on its side, with its legs fanned out to one side, the spider’s body represents the present moment, and each leg a different version of how things might go. Whatever we face, there are always a range of ways it can go, some better, others worse. If things have worked out badly, and you find yourself heading down a less welcome spider leg, it can help to remind yourself that even from here, things can still develop in different ways. This leads to the double spider – the first acknowledging the downslope of a turning for the worse, and the second offering a range of versions of how the next bit of the story might go (see diagram). The second step is to choose what you hope for. So long as we’re able to make choices, then the guiding energy and purpose of supporting hoped-for futures can act through us. The third step is to take action to help your preferred version of the future become more likely.

We can look at a piece of land and recognise that it can be used in different ways. We can do the same with our words and concepts. When facing worries about the world, the questions, ‘Are you hopeful?’ and ‘What do you hope for?’ take us in completely different directions. Hopefulness is about our assessment of probability, and when its levels are low, that discourages people from taking action. ‘What do you hope for?’ is more motivating, helping you tap into your guiding energy and purpose. Your hope can happen through you when you act on its behalf.

There’s an important difference between ‘make your hopes happen’, and ‘make your hopes more likely’. When you look at an action by itself, it is easy to dismiss its value with thoughts like ‘that won’t do much’. Questions like ‘What does that action contribute to? What’s it part of? And what happens through that?’ can help you recognise how a larger story of change can happen through our smaller steps. Active Hope is the practice of taking these steps; like permaculture, it is something we ‘do’ rather than ‘have’.

When thinking about our ability to make a difference in the world, we can apply the spider diagram to ourselves. There are a range of versions for how things can go. What is the best that could happen? If it were to work out as well as you’d hope, what might that look like? And how can you make that more likely or head in that direction? If you’d like permaculture to happen through you in the best possible fashion, you might look for ways to practice, build in support and seek out training. Can we do the same with hope? And if so, what might that lead you to do?

Chris Johnstone’s important book, Active Hope, co-authored with Joanna Macy, is now available with a 2022 update. It explores how to face the mess we’re in with unexpected resilience and creative power. More info here: www.activehope.info

Chris Johnstone is an online educator at CollegeOfWellbeing.com, ResilienceTraining.net and ActiveHope.Training. His free video-based online course Active Hope Foundations Training is available at ActiveHope.Training